Researchers from the University of Michigan and NASA's Goddard Institute have discovered that a single shale oil plant is to blame for roughly 2 percent of all airborne ethane - a gas that can damage air quality and affect climate.

The Bakken is a a large oil field situated in the 200,000 square-mile basin that runs across North Dakota, Montana, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. The oil industry took to the large swath of land in a hard and fast way: production increased by a factor of 3,500 between 2005 and 2014 - though it's plateaued over the last couple years. This rapid-fire increase has made the Bakken one of the most concentrated emission areas in the world - recent studies showed that the Bakken generates approximately 250,000 tons of ethane per year.

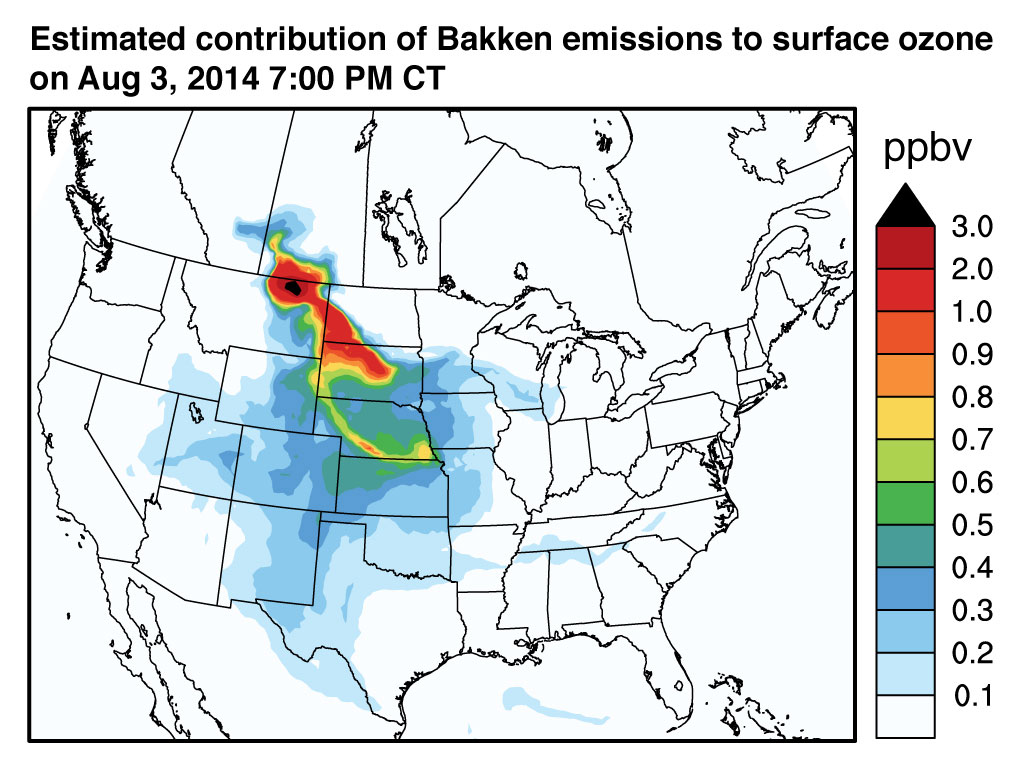

Eric Kort, an assistant professor at the University of Michican, believes that the emissions from the Bakken alone has caused a significant shift in the global airborne ethane concentration. "Two percent [of the global airborne ethane] might not sound like a lot, but the emissions we observed in this single region are 10 to 100 times larger than reported in inventories. They directly impact air quality across North America."

So, how can ethane cause harm? When ethane mixes with sunlight and atmospheric compounds, ozone is formed. When the ozone descends to the earth's surface, it can be extremely harmful to the human respiratory system upon prolonged exposure. Ozone is also purported to play a significant role in climate change, as it is considered a greenhouse gas. Global ethane levels were on a downwards trend up until fracking started to gain momentum around 2009. Since then, ethane levels have been rising - and when researchers discovered how much the Bakken was spewing, the significant global uptick in ethane content was explained.

The Bakken isn't the only shale field outputting extraordinary amounts of emissions, but it is the largest. Very recently though, production has hit a slight decline. Bad news for the North Dakota and Montana oil industries - but perhaps welcome news for the average human lung.

For more information, see the original study: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/2016GL068703/epdf